The meaning of life

The Bissonnette case before the Supreme Court will put life sentences with consecutive parole ineligibility in the spotlight.

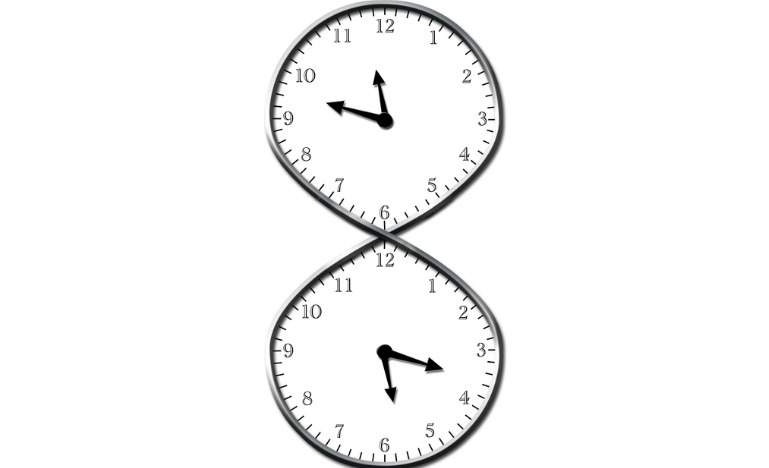

Just what is a life sentence, anyway?

The Supreme Court will be tackling precisely that question when it hears an appeal over the sentencing of Alexandre Bissonnette, the 31-year-old responsible for a mass shooting that claimed the lives of six worshippers at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City.

In so doing, the court will revisit a question that Canada hasn't properly dealt with since it abolished the death penalty: Should the worst-of-the-worst be eligible for parole after 25 years?

Bissonnette's culpability was never, really, in doubt. The more pressing question turned on whether he would be charged with murder or whether prosecutors would pursue terrorism charges.

When it came time to devise an apt sentence for his six counts of first-degree murder, the Crown wanted Bissonnette to serve two of those charges consecutively — meaning he would be sentenced to life in prison without the eligibility of parole for 25 years, twice. It would be 50 years before Bissonnette could plead his case for even conditional release.

Bissonnette's lawyers fought to have him serve all six counts concurrently, meaning he would be eligible for parole after 25 years.

The debate over what constitutes a life sentence is a relatively new one. There have been relatively few instances in the last decade where cases like Bissonnette's were adjudicated. The law on consecutive sentences has only been on the books since 2011, when the then-Harper Government introduced the Protecting Canadians by Ending Sentence Discounts for Multiple Murders Act.

Just a few years after the law came into force, in 2014, the Moncton shooter Justin Bourque was sentenced to three consecutive first-degree murder sentences, leaving him ineligible for parole for 75 years. It was one of the harshest sentences issued in Canada in a half-century. Bourque will be over 100 when offered the option to apply for parole

In 2019, serial killer Bruce McArthur was sentenced to his eight counts of first-degree murder concurrently — but for a 70-year-old, there isn't much difference between a 25 and a 50-year sentence.

Bissonnette's case was unique because Quebec Superior Court Justice François Huot opted to split the difference, sentencing Bissonnette to life in prison without eligibility of parole for 40 years.

In so doing, Huot read in a new set of principles to the Act.

If each first-degree murder sentence extended parole ineligibility for another 25 years, Huot wrote, "what sentence could be contemplated, hypothetically, for someone having stabbed 10 people at a shopping centre? 250 years of ineligibility? 350 years? What about a hitman who, strictly for financial gain, killed 25 people over a 10-year period? 625 years of ineligibility? 800 years?"

In settling on 40 years, Huot pleased nobody. The Attorney-General appealed, insisting on 50 years, while the defence appealed, demanding 25.

At the Court of Appeal, the justices did away with Huot's effort to read in proportionality.

"The discretion conferred on the judge by a legislative provision," the court wrote, "cannot be used to confirm the provision's validity if the sentence resulting therefrom is intrinsically unacceptable by nature."

The appeals court declared the 2011 Act unconstitutional, under sections 7 and 12 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and offered a cautionary word to the debate around the issue: "it is important to note that the sentence is not one that imposes 25 years of imprisonment, but rather a sentence of imprisonment for life, without the possibility of applying for parole before 25 years."

The Supreme Court will now have to decide whether one charge of first-degree homicide should, in the eyes of a sentencing judge, be roughly the same as ten or twenty counts.

"We put in the 25-year minimum before we had parole," notes Matthew Shadley, a partner at Shadley Bien-Aimé in Montreal. "That was the compromise that we made when we took out the death penalty."

Indeed, as the appeals court noted, 25 years was a particularly harsh benchmark that sought to balance the elimination of the death penalty. "Data showed that the average mandatory term actually served at that time was from 10 to 15 years," the justices note. "Parliament chose a 25-year period."

Consecutive sentences were designed to stretch beyond those 25 years, but in a rather clunky way — judges can hand down more strict penalties, but only in increments of 25 years. Justice Huot only got to 40 years after finding the provisions unconstitutional and reading in his own interpretation of the law.

"The legislation actually doesn't give sentencing judges the ability to split the baby," says Lindsay Board, an associate at Daniel Brown Law in Toronto. "That's not something that's permitted."

The debate around 40 years of parole ineligibility versus 50 years is fundamentally "an attempt to fix a problem that didn't exist in the first place," she says.

And as the Court of Appeal stressed, Board notes, "just because you're eligible for parole doesn't mean you'll get it." The courts have proven, consistently, that they are skeptical of offenders' initial requests for parole. Serial killer Paul Bernardo became eligible for parole three years ago, but had his first application quickly denied. His next hearing comes up this month.

"In a lot of instances, we see the parole board doing what they're supposed to be doing," she adds.

Even if the risk of serial killers and terrorists being released after 25 years is, essentially, nil, there is still a clamouring to find a way to say something a little more significant about these fringe cases. To denounce and deter those crimes and offer solace to the families that the killer won't ever be let free.

As Board notes, that power already exists: "If you want to designate someone as a dangerous offender, and give them that sort of an indeterminate sentence, that's an option."

A better solution, says Shadley, would be to have longer parole ineligibility periods, as is the case for hate crimes or terrorism offences. "I would prefer to see this regime come out of Parliament, rather than from the judge," he cautions.

At the same time, Shadley notes that there are diminishing returns when it comes to deterring crime with harsh sentences.

"For that logic to make sense, you'd have to say Bissonnette would not have shot up a mosque if he knew he was going to get 50 years instead of 25," Shadley says.

In effect, conversations around deterrence are usually a mask for, what Shadley calls "vengeful lust."

Indeed, in a study of Canada's terrorism sentencing regime, three University of Calgary academics — including law professors Michael Nesbitt and Meagan Potier — found that efforts to underscore the severity of terrorism tended to overshadow other, serious, considerations, such as "such as youth, or the possibility of rehabilitation, to the background in terms of mitigating importance."

They write that: "In the context of terrorism offences, we have seen a judicially-imposed mandatory minimum taking shape, despite a general judicial hesitancy towards mandatory minimum sentences."

Indeed, the 25-year minimum is designed to temper those instincts.

"I don't know where this idea came from, that 25 years without parole is not sending a clear message," Shadley says, adding that perhaps a longer period — say, 35 years — could be more apt.

But suppose we accept that the Parole Board of Canada works well in ensuring dangerous predators and serial killers are not released before is appropriate. In that case, we could consider other solutions, such as giving victims more of a hearing at sentencing. Or perhaps, Shadley suggests, incorporating particular considerations around hate crimes for parole hearings.

"I think a lot of those tools already exist, but I think sometimes they're not being used," Board says.

Wherever the Supreme Court lands, it's unlikely any sentence will ever seem well designed to address instances of mass violence.