Merger reviews: Abandoning the Chicago School

Competition authorities in Europe, the U.S. and Canada are grappling with renewed pressure to intervene and enforce antitrust laws more aggressively.

Strictly speaking, antitrust law is about protecting the welfare of consumers so that they can have access to competitive markets. Not so long ago, the prevailing view was that governments should stay out of the way as much as possible for that to happen, lest they do more harm than good. Better to rely on free markets than on antitrust regulation to rein in the dominance of potentially abusive companies. At least, that was the approach promoted by scholars hailing from the so-called Chicago School – and popularized by law professors Robert Bork and Richard Posner, who later shaped the case law around antitrust in the U.S. after they were appointed to the bench.

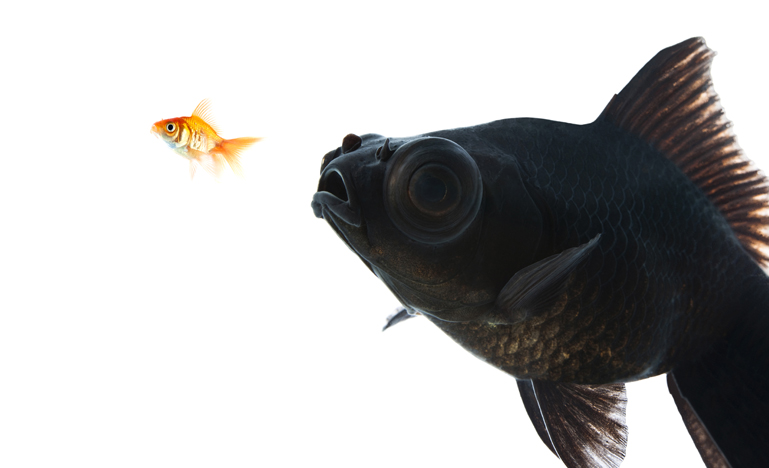

It's a view that has lost its lustre lately. Making a comeback is a more old-fashioned assessment that "big is bad."

"There's this view that this hands-off attitude has allowed big business and consolidation to grow," says Elizabeth Bailey, an economist with NERA Economic Consulting, based in Berkeley, CA. Speaking at last month's CBA Competition Law Conference in Ottawa, Bailey explained that there are growing concerns that antitrust regulators have cleared too many merger deals and overlooked new forms of competitive harm. That has led to higher prices and poorer outcomes for consumers, the argument goes, because markets aren't quite as self-correcting as Chicago School advocates have suggested.

A mix of populism and an increasingly vocal and influential "techlash" movement is also pressuring policymakers around the world to rethink antitrust enforcement, and emphasize public interest issues more, such as privacy concerns, protecting jobs, and promoting national champions. Most obviously, sentiment around mega-platforms has soured, particularly in the wake of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica privacy scandal revealed in 2018.

Now authorities are grappling with how to rein in Google, Amazon, and Facebook.

Germany will be implementing an ambitious new digital antitrust law to regulate online markets effectively. The EU's Competition Commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, is considering a proposal that would force digital platforms suspected of anti-competitive behaviour to show they are using people's data for the public good, instead of requiring the Commission to show the damaging effects on consumers. In the U.S., Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are also calling for stronger action to curb the power of tech giants.

In September, Canada's Competition Bureau published a call-out for information about any conduct in the digital economy that may be harmful to competition. Earlier this summer, the Bureau appointed George McDonald as its first chief digital enforcement officer. His job is to protect Canadians from deceptive marketing and fraud online.

The piling on against Big Tech may have made competition law cool again. But in truth, antitrust authorities have been flexing their muscles for a while now – even before mega-platforms became targets. In 2016, AT&T won approval for its merger with Time Warner, even though the U.S. government tried to stop the $85.4 billion deal. Last year, Qualcomm Technologies had to walk away from a $44-billion bid to buy its rival, NXP Semiconductors, after failing to get clearance from China's State Administration for Market Regulation.

European authorities have been especially aggressive, invoking new theories of harm in their merger reviews and other antitrust probes.

Historically, for instance, anti-competitive enforcement has focused on horizontal mergers where we see consolidation happen within the same industry. The European Commission has shown more resolve lately in challenging vertical mergers, which involve companies at different stages of the supply chain. In 2016, it approved the merger between Microsoft and LinkedIn, but only after Microsoft made several commitments so as not to shut out LinkedIn's competitors.

Antitrust authorities are also turning their attention to what's known as "killer acquisitions" – which involve incumbent businesses snapping up smaller nascent companies that have emerged as competitive threats. The acquirer's intent here is often to send the target's pipeline product to the gallows.

The EC has also been probing other harmful effects on innovation. When assessing the 2017 tie-up between Dow and DuPont, it looked at whether it would have the effect of reducing innovation more generally. According to Frank Montag, of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in Brussels, the concern was that "in a concentrated industry with a high degree of R&D activity and high barriers of entry, a merger between two of the top five players will lead to a reduction in overall competition." The EC cleared the deal but forced DuPont to sell a significant portion of its R&D facilities.

Amidst all of these flashing lights, the question for Canada's Competition Bureau is how it should go about joining the global bandwagon by ramping up its enforcement activity against mega-platforms, particularly given its limited resources.

"The Bureau is outgunned and under-resourced in the whole area of digital markets expertise," said John Pecman during one panel discussion. According to the former Commissioner of Competition and now a senior business advisor at Fasken, the Bureau's budgets "are continually being eroded."

"[Should we] be going after the same platforms and the same conduct that the U.S. and European enforcers are going after?" asked Michelle Lally, a partner at Osler, during another session. "I don't think so, because if there is a [European or U.S.] remedy at hand, it in itself may be implemented by the platform to the benefit of Canadians."

Lally further notes, somewhat tongue in cheek, that Canada is one of the few countries that has a defence that allows efficiency enhancing mergers and collaborations between competitors. "We should be efficient here and rely on Europe and the U.S.," she says. "The Bureau should focus on Canada and on anti-competitive conduct that is affecting the process in Canada."

It's a view shared by Chris Cook, of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP in Brussels. Cook rejects the notion that the bureau piggybacking on the work of better-endowed enforcement agencies in other countries should be viewed with scorn. "It's just better bang for your buck to get involved in cases that are otherwise going to fall through the cracks," he says.

As the pendulum swings away from the Chicago School approach, another thing to keep in mind is evaluating our ability to identify deals that will cause harm. Economists use inference and data to guide them, says Bailey, but as part of that process, there are going to be errors, particularly in more disruptive economic environments.

"What kind of errors are we comfortable making," she says. "Are we more comfortable under enforcing and letting deals go through because we think it could be more costly to block a deal that might, in fact, be pro-competitive? Or do we over-enforce? That's the tradeoff."