Booming energy practices

The $15-billion Canada Growth Fund has energy lawyers focused on helping build the clean economy.

The launch of Canada's $15-billion investment fund to promote growth in the "clean economy" will provide more opportunities for homegrown innovation and spur legal work to support that, say energy lawyers.

The new Canada Growth Fund "is certainly exciting to me as it would allow for a lot of Canadian driven technologies, development projects, to start to develop a Canadian expertise area," says Elizabeth Burton, Gowlings WLG's financial services practice group leader in Calgary.

Corporate lawyers with expertise in the energy industry will be front and centre working on the structuring of new companies and projects. She says they'll be busy with mergers and acquisitions, consolidations, and partnerships between municipalities or traditional oil and gas providers looking to reduce their footprint and transition energy usage. Intellectual property development will also be part of the mix.

Along with financing plans, environmental, indigenous consultation and regulatory matters will also be crucial for companies looking to take advantage of the new program, says Burton.

Alberta's recent pause on approvals of new renewable energy projects is indicative of the regulatory and infrastructure issues around emerging clean energy technologies, she says, which opens up opportunities for work on the legal aspects of setting them up.

The Canada Growth Fund was announced in the 2022 federal budget in response to America's Inflation Reduction Act. The arm's length public investment vehicle is a subsidiary of the Canada Development Investment Corp. and is led by Patrick Charbonneau and other investment professionals at the Public Sector Pension Investment Board (PSP Investments). It was capitalized with $15 billion to be deployed over the next five years for Canadian projects and technologies.

The fund is part of the government's strategy to ensure Canada remains competitive with the U.S., says Fasken counsel David Heurtel, a former Quebec environment minister. He noted massive investments in electric vehicle battery plants in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia as other "aggressive" examples of the government's investments in clean tech.

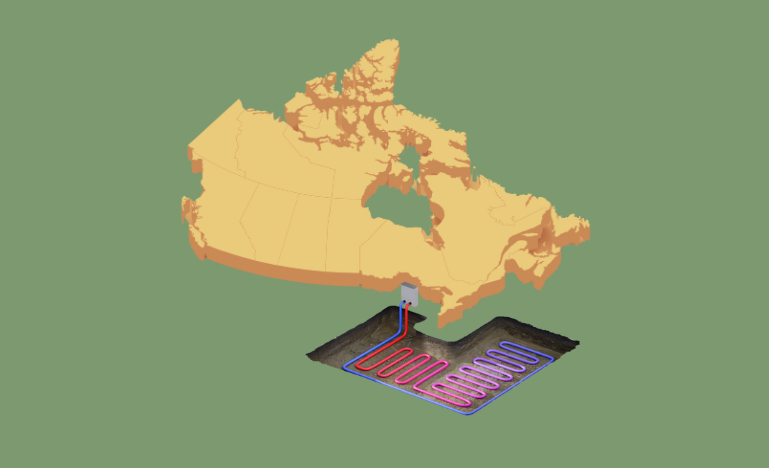

The CGF announced its first venture in October, a $90-million investment in Calgary geothermal energy company Eavor Technologies Inc. Eavor has developed the Eavor-Loop, the world's first scalable technology for closed-loop geothermal power and heat generation, which captures geothermal energy to produce steady and dependable heat and electricity without any emissions, according to the government's announcement.

Heurtel thinks the CGF will be effective in boosting new energy projects. Its success hinges on its ability to balance risk management and innovation while easing the integration of fund resources with other measures.

In Canada, financing of clean tech projects has traditionally been hampered by uncertainty with the value of carbon credits, political uncertainty around carbon pricing mechanisms, and other changing regulations across different jurisdictions, says Heurtel.

While the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act stands out as a significant source of funding for cleantech, governments in Australia, Europe, Japan, and South Korea have also created funds to support clean energy innovations. "It would be very hard [for Canadian entrepreneurs] to be competitive without some kind of equivalent program," says Burton, whose finance practice has a heavy component relating to energy transition.

It's part of the CGF's mandate to support less mature technologies and processes, which Burton says are the ones that have a harder time establishing themselves and getting that initial funding.

The CGF, like the Canada Infrastructure Bank model, is set up to de-risk investments, explains Burton. In traditional financing, banks' risk in putting money forward is offset by the rates and securities they take, but with new technologies, mainly on smaller or startup projects, that doesn't work. "What these types of structures do, and I believe Canada Growth Fund is fairly committed to it, is they will reduce the upfront costs and take the pricing components down or provide equity or other flexible models."

She says she's not seen anything specific on it yet, but her understanding is the fund will also provide support on the "offtake," offering some "certainty as to who's going to buy this energy or who's going to support the revenue stream on the other end."

Heurtel cautions, however, that it's a time of financial uncertainty. While Canada is putting billions into the fund, it's still only a drop in the bucket compared to the US$390 billion in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. The government needs a fulsome strategy to promote clean tech investments here, and he wants to see how governments react to external factors such as inflation and labor shortages. "It's going to be very interesting to see where the market goes and where the money goes," he says.

Clients are excited about the prospects of the CGF and are figuring out how to navigate the opportunities and understand what it means practically for them because there's still a lot of uncertainty about how it will be deployed, says Burton.

Lawyers and law firms need to ensure they understand the program by connecting to industry groups and others to be aware of new program details as they emerge, she says. To offer value to clients, "you need that familiarity on what the options are in the first place," she says.