Whose duty to consult?

It’s being left up to resource companies to negotiate access to aboriginal land. Is government outsourcing DTC to the private sector?

Hindsight says everyone involved probably should have seen it coming.

In June 2012 — more than a year before Cliffs Natural Resources Inc. suspended its planned $3.3-billion chromite-mining operation in Northern Ontario, putting the entire Ring of Fire mining rush on the bubble — Northern Superior Resources quietly halted exploration of its gold claims in northwestern Ontario.

The junior miner was mired in a dispute with the local Sachigo Lake First Nation over compensation for exploration activities in Treaty 9 territory. Under Ontario’s Mining Act, mining start-ups on aboriginal land can proceed only after consultation with local aboriginal communities, which the company did. But things went off the rails.

The company found itself embroiled in disputes with the community over invoices and fees. At one point, the First Nation blocked two Northern Superior staffers from flying out of the community for a day.

In October 2013, Northern Superior filed a $110-million statement of claim against the Ontario government in a case that maps one of the deepest fault lines in the relationship between the Crown and Aboriginal people: the legal doctrine of duty-to-consult (DTC).

“My hair’s a little greyer than it was a year back. But that’s the junior mining sector for you,” says Tom Morris, CEO of Northern Superior. “Suing is not something I wanted to do, believe me.”

Northern Superior argues that provincial or federal governments — not resource companies — must take the lead in negotiating access to traditional land. In its statement of defence, the province argues that Northern Superior went in with its eyes open and any liability in terms of DTC would be owed to the First Nation, not Northern Superior.

Who’s right? Good question.

Across Canada, aboriginal communities and resource companies are struggling to apply DTC in a fast-changing legal and commercial landscape. And they’re doing it largely on their own; for the most part, governments seem to be leaving Aboriginal people and the private sector to work things out for themselves, with mixed results.

“I think that provinces and the federal government have been extraordinarily slow in implementing duty-to-consult,” says Bob Rae, the former interim leader of the Liberal Party who now serves as chief negotiator for the Matawa First Nations in their dealings with the Ontario government.

“Governments tend to download their DTC responsibilities. They say to companies, ‘Go off and talk to the First Nation, and that fulfills our obligation to consult.’ But DTC can’t be privatized that way. It’s taking governments a very long time to come to grips with this.”

But the pressure is on: DTC affects a vast number of resource projects across the country, from exploration starts to huge, multi-billion-dollar projects like the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline in B.C. And Northern Superior likely won’t be the last resource company to take a government to court over DTC; in December 2013, the B.C. Supreme Court ordered the province to pay $1.75 million to Moulton Contracting, a logging company which sued B.C. for failing to meet its DTC obligations before a First Nation blockade halted operations.

“The Moulton decision was amazing — a private company holding a government to account over DTC — and I suspect you’re going to see a lot more cases like this as the industry pushes back,” says Tom Isaac, the Calgary-based head of the aboriginal law practice at Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP.

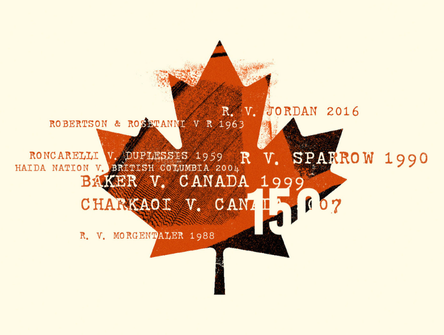

The politics surrounding duty-to-consult may be in flux, but the law itself is pretty clear. Duty-to-consult is rooted in Section 35.1 of The Constitution Act, 1982 — the clause that recognizes and affirms aboriginal and treaty rights — but it’s shaped mainly by two key 2004 Supreme Court decisions: Haida Nation v. British Columbia and Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia.

In the Haida case, the First Nation took issue with a provincial government tree-farming licence in an area over which the Haida claimed aboriginal title. The SCC ruled that the Crown — in this case, B.C. — has a “duty to consult with Aboriginal peoples and accommodate their interests” in cases where a government decision will, or may, abrogate an aboriginal right. Haida upped the ante both by asserting DTC as a requirement and by saying it applies even in cases where aboriginal title hasn’t been established.

“Before Haida, the Crown and industry tended to lean toward the lowest level of consultation,” says Merle Alexander, a partner and expert in aboriginal resources law with Gowlings LLP in Vancouver and a member of the Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation. “The big question was whether the Crown had an obligation to consult in cases where a First Nation’s rights had not been proved. Haida established that it did.”

The Taku River decision — issued the same day as Haida — helped draw the boundaries of DTC. A mining company wanted to build an access road to a worksite across Tlingit traditional territory in B.C. The Tlingit and the mining company took part in a three-year environmental review process that concluded with the issuance of a build permit. The Tlingit’s attempts to quash the project ended at the Supreme Court, which ruled that, while the First Nation had a strong prima facie case, the Crown had met the test of DTC.

Haida and Taku River together established three essential features of DTC: that it’s a Crown obligation, that it applies to asserted aboriginal rights as well as established ones — and that it’s not a blanket veto. They gave the courts a “spectrum” of rights, a tool to determine how to apply DTC.

“Think of a chart plotted along two axes,” says Larry Innes, aboriginal and environmental law practitioner at Olthuis, Kleer, Townshend LLP in Toronto. “One axis is the strength of the claim, ranging up to high-order rights concerning things that are integral to a culture, such as the location of an old aboriginal village or ceremonial ground. The other axis charts the intensity of the impact, from low-order disruptions all the way up to something extremely disruptive, like an open-pit mine.”

DTC isn’t a veto — but whether it implies a requirement for aboriginal consent at the high end of the spectrum is a topic of fierce debate in aboriginal law circles.

“Haida quite clearly stated that DTC is not a veto and anybody who tells you different is dead wrong,” says Isaac.

Merle Alexander is not convinced. “In certain circumstances, depending on the project and the strength of the claim, DTC could amount to an aboriginal veto,” he says, adding that Haida held that proven, established rights imply a requirement for consent — essentially an aboriginal veto.

Most experts agree that Northern Gateway and other pipeline projects will test both the strength of the veto argument and the degree to which the Crown is required to be directly involved in DTC. Haida held that the Crown could delegate “procedural aspects” of DTC. British Columbia has taken that ball and is running with it, Alexander says, requiring project proponents to carry out DTC through the environmental assessment process.

“I have heard proponents state that they are legally required to fulfill the delegated duty-to-consult,” he says. “So, by legislation and policy, the Crown is delegating its constitutional requirements to third parties.”

Blame inertia, says Judith Rae, a treaty law practitioner at Othius Kleer Townshend LLP in Toronto. She has represented First Nations in Northern Ontario.

“Governments are vast institutions and they change direction slowly,” she says. “They’re used to ignoring First Nations, to making decisions around them rather than with them.

“It’s a poor approach. It amounts to telling First Nations: ‘We’re here to game the system. We’re not taking this seriously.’ Now we’re starting to see the slow realization that they need to engage, but, by and large, both levels of government are still struggling with the concept.”

Ottawa was relying on the regulatory review process and Enbridge’s own consultations to meet its DTC obligations on Northern Gateway — yet hours after the National Energy Board review panel released a report setting more than 200 conditions for the $7.9-bilion project to proceed, First Nations along the pipeline corridor were threatening lawsuits (at least two have since filed). And that was after the federal government’s own special adviser, Doug Eyford, issued a report reminding Ottawa of its DTC responsibilities.

“There’s no question that the federal Crown has failed completely in its DTC responsibilities with respect to Northern Gateway,” says Bob Rae.

Tom Isaac disagrees. “Yes, the burden of DTC falls on the Crown, but the project proponents can assist the Crown in carrying it out,” he says. “My view is that the consultations conducted on Northern Gateway have been among the most robust in the country.”

Of course, a right that doesn’t amount to a veto in law can still operate as one. Legal action that delays a project can be as effective as a court order — especially if the project proponent is a small company with limited resources. And it’s those smaller firms — junior miners like Northern Superior, for example — that feel squeezed between aboriginal anger and government apathy.

“If you’re travelling the world looking for billions of dollars to invest in a mining project, your investors will want — at a minimum — assurances that your rights over the land and in the minerals are solid, and that your permits are not open to attack,” says Katia Opalka, a specialist in Aboriginal and environmental law at Lavery de Billy LLP in Montreal.

“Consultation is not their job or their area of expertise — but what’s at stake is time and money, and time is money. That’s why resource companies often work directly with communities in the project area to map out a plan for information-sharing and consultation. And they do this well in advance of getting started on the regulatory process.”

New Millennium Iron Corp., a junior established in 2003 to exploit two iron deposits about 700 kilometres northeast of Montreal, has negotiated accommodation deals with five separate aboriginal communities, covering everything from financial compensation, training and employment to cultural aspects like special facilities for spiritual practices. Neither the Quebec government nor Ottawa were involved.

“And it was a huge expense to us — hundreds of thousands of dollars — because we were covering our own negotiations and those of the First Nations,” says Paul Wilkinson, New Millennium’s senior vice-president of environmental and social affairs. “We don’t think it’s appropriate for a private company to be negotiating arrangements related to aboriginal rights.

“But if we hadn’t done it? I think the outcome would have been that [the First Nations] would have blocked the project.”

Small resource companies aren’t the only ones complaining of Crown disengagement. Small aboriginal communities short of funds and expertise often struggle to get good deals out of resource projects.

“You’ve got First Nations with limited resources, small populations and limited skill sets trying to negotiate massive agreements for huge sums with small mining operations that might be nothing more than a couple of engineers working out of someone’s garage,” says Ken Coates, aboriginal law expert at the University of Saskatchewan.

The impact and benefit agreements negotiated between resource companies and aboriginal communities are usually kept secret. “As a result, a company might enter an agreement from an unrealistic financial perspective,” says Wilkinson. “Which is why the game needs rules and the Crown has to be the one to set them.”

In fact, many people on all sides of the issue agree on the need for clear national rules — or at least firm guidelines — for discharging DTC. Some suggest the answer might be a quasi-government agency positioned between the Crown, Aboriginal people and project proponents.

“Part of the problem here is that it’s never completely clear whether this is a federal or provincial responsibility,” says lawyer Tony Knox of Knox & Co. in Vancouver. “Maybe what we need is for the federal and provincial governments to get together on a national body that would stand between the project and the courts — a group of people with specialized knowledge to whom judges could defer, much the way they defer to, say, securities commissions.”

Nonetheless, he adds, private companies probably will be asked to take the lead in DTC negotiations for two simple reasons: It’s their money, and they need a forum to build a relationship with aboriginal communities based on mutual benefit and respect.

“Every country has to work out how to deal with what I call the ‘social licence gap,’” he says. “I remember a conference many years ago about resource law and aboriginal communities. I was explaining how we do things in Canada to a lawyer from another country. He said, ‘That’s very interesting. We don’t do consultation. In my country, the government does napalm.’

“Bad as things can get in this country, you’re much better off being an aboriginal community fighting to defend your constitutional rights here than just about anywhere else in the world.”

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article could have been misconstrued to mean that the duty to consult is with First Nations only, and not all Aboriginal people, including the Metis and Inuit. We regret the error.