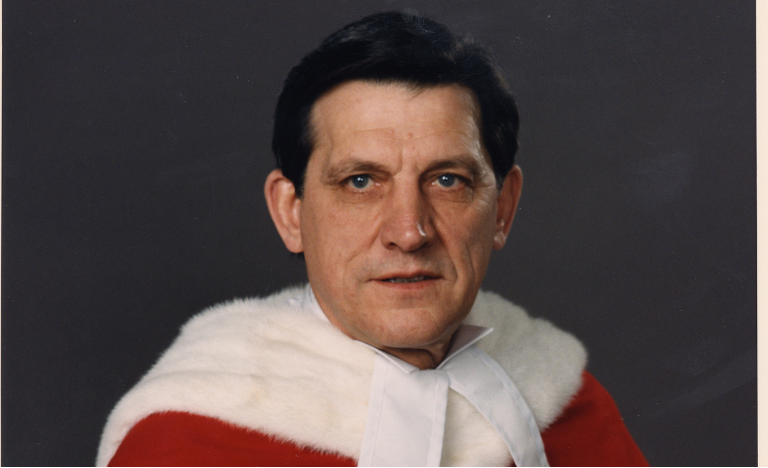

‘A great human being, on many counts’

Former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Gérard La Forest believed the rule of law is essential not only to a just society, but the functioning and survival of Canadian democracy

Former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Gérard La Forest is being remembered as “a great jurist and great human being” whose eloquent judgments have left an enduring legacy in Canadian jurisprudence.

A legal scholar, public servant, and jurist, La Forest served on the Supreme Court from 1985 until 1997. He passed away peacefully on June 12 at the age of 99, surrounded by his daughters at home in New Brunswick.

“My colleagues and I mourn the loss of Justice La Forest — an exemplary jurist whose compassion deeply informed the Court’s decisions on issues that touched the lives of all Canadians,” Chief Justice Richard Wagner said in a statement.

“As a distinguished appellate judge, legal scholar and public servant, he brought unmatched intellect and experience to the Supreme Court of Canada. His eloquent judgments, spanning many areas of the law, have left a profound and enduring legacy in Canadian jurisprudence. He will be remembered with great respect and admiration.”

La Forest was born in Grand Falls, New Brunswick, on April 1, 1926, and studied law at the University of New Brunswick. He was called to the province’s bar in 1949 and was named a King’s Counsel in 1968. As a Rhodes Scholar, La Forest also studied at Oxford University to earn a BA in 1951. He later completed an LLM at Yale University in 1965 and a JSD at the same university in 1966.

He served in the federal Justice Department after a short period in private practice. He later entered legal academia and became dean of law at the University of Alberta. He returned to the federal public service in 1970, serving as assistant deputy attorney general until 1974. Along the way, he spent five years as a member of the Law Reform Commission of Canada.

La Forest was appointed to the New Brunswick Court of Appeal in 1981 and elevated to the Supreme Court of Canada on January 16, 1985.

Former Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin came to know him when she was appointed to the Court in 1989.

“The man I encountered and came to know deeply in the years that followed was a great human being, on many counts,” McLachlin said in an email.

“He possessed one of the finest legal minds I have ever encountered, shaped by a deep understanding of Canada’s dual legal traditions and marked by clear thinking, wisdom and creativity. He played a seminal role in shaping the jurisprudence that defined the new Charter era.”

She added that La Forest was a devout Canadian who believed that the rule of law is essential not only to a just society but also to the functioning and survival of Canadian democracy.

“He was a kind and loyal man, devoted to his family and the many he counted among his friends,” McLachlin said, adding she’ll never forget the kindness he and his wife Marie showed her when she came to the Court, nor the long conversations on fine points of law they enjoyed in the years that followed.

“Gerald La Forest was a great jurist and great human being. He may have left us, but he lives on the words of the judgments he authored and in the memories of those who knew him.”

Former Supreme Court Justice Frank Iacobucci says La Forest “was an outstanding jurist, as a scholar, and a judge,” who had many accomplishments before even going on the bench.

He fondly recalls playing tennis with La Forest and his “wonderful” wife.

University of Waterloo professor Emmett Macfarlane, who wrote Governing From the Bench about the Supreme Court of Canada, says La Forest in many ways epitomized a judge with an academic background, when several were appointed during the governments of Pierre Elliot Trudeau and Brian Mulroney.

“He was a nuanced thinker,” Macfarlane says, noting La Forest wrote a lot of concurrences in constitutional law cases, which is interesting because while he agreed on the outcome, he seemed to be keenly interested in articulating somewhat distinct reasons for particular outcomes.

“Judges don’t necessarily write for the pure pleasure of writing. They do that because they think they have something important to say, and the number of concurrences he wrote, at least in public law cases, speaks to his academic background.”

Admittedly, that can be a double-edged sword, given that some people will say academic judges overcomplicate things and that there could be such a thing as being too nuanced in one’s thinking.

La Forest wrote the leading decision in Mckinney v. University of Guelph, where the Court found that the Charter doesn’t apply to universities, at least for the purpose of mandatory retirement rules, but that it does apply to colleges.

“The Court was making a distinction about the degree of direct government control based on things like how many members of a board of governors is a government appointing,” Macfarlane says.

“It was a very fine distinction that I think a lot of people would look at a broadly worded provision about what the Charter applies to and wonder how it applies to public colleges but not universities.”

Macfarlane says the case is an example of a risk of overly nuanced thinking.

His favourite set of reasons from La Forest is the dissent in the Provincial Judges Remuneration Reference. There, the Court invented a new constitutional rule that governments seeking to adjust judicial salaries need to create and listen to the recommendations of judicial compensation committees that are independent from government.

“It was a very controversial decision in part,” Macfarlane says.

“While the Court grounded its ruling in judicial independence, it’s kind of a radical, very expansive idea of judicial independence in the context of cases that really dealt with governments’ broader efforts to deal with salaries writ large.”

Judges and courts weren’t targeted with across-the-board cuts, but he says it remains one of the most “activist” decisions in the Court’s history.

“La Forest’s dissent really goes after his colleagues a bit for what amounts to judicial overreach, and I’m pretty sure he noted the potential self-interest involved in the issue the Court was facing, and really about the nature of judicial independence,” Macfarlane says.

“I thought it was a dissent that really gave some thought to the institutional relationships and the separation of powers—important concepts that reflected some sober thinking on his part in a Court that in that case was a bit run amok.”

Adam Dodek, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, echoes that sentiment.

“His dissent in the Provincial Judges Remuneration Reference is a tour de force that stands the test of time,” he said in an email.

“It serves as an homage to judicial humility and a caution against judicial overreach.”